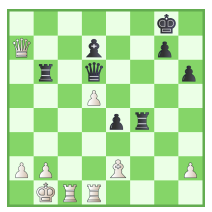

Just a few fun positions to find a tactic from blitz/bullet games of mine.

White to move

Continue reading Bookmarks #5Just a few fun positions to find a tactic from blitz/bullet games of mine.

White to move

Continue reading Bookmarks #5Going to work on four more problems.

But first! Last time on Problem Solving I got the main ideas on the first one but failed to calculate that 1…g5 was the best option, am informed I got 2 and 3 correct, and bungled 4, undervaluing the pressure or 1.Re1. All in all a very solid result on complex positions. I sometimes say the best puzzle solving rate is the lowest your ego can handle, which is somewhere around 50%. But this isn’t quite right, as if you go much lower then you’re probably not engaging with/understanding enough of the problem to learn from the solutions. So I think the ideal rate is probably 50-75%, but if 50% feels terrible to you and 75% feels okay for your ego, try to find problem sets where it’s 75% not 50%! Anyway the main point of these is to find the ideas. Whether or not we pick the best move, let’s make sure we understand the possibilities.

Okay, onto the new four problems.

#5

Continue reading Problem Solving 2Taken from Volotikin’s Perfect Your Chess. This kind of position makes me so happy.

Black to move

Continue reading A Strategic PuzzleWarning: the following post is incomplete, I stopped thinking about the QGA and only made it halfway through. Still, I like the work I did and thought it better to do a partial post then none at all!

Some years ago every GM course or recommendation I came across against 1.d4 opened with “I am recommending [insert variation here] because it is the best combination of sound and unknown, except the QGA of course.” Hear this a few times and you start thinking you should be playing the QGA. At around the same time FM Nate Solon showed me a few games of his in the QGA where he was equalizing or better out of the opening, with regularity, against IMs in classical games. I thought, I could do that! And tried to repeat the lines he played. In the exact lines he showed I did fairly well, elsewhere where I had to try my own preparation, not so well. This emerged a few times we prepared together actually; in the QGD Janowski with …a6 we independently did some prep and then checked it together. His lines were more concise and to the point, focusing on the key ideas and standard development schemes, they far more useful to preparation than my scattered lines. It’s not that my lines were wrong, but they were far less useful than his narrower presentation. His understood and showed the ideas and goals clearly; mine were mostly what the computer said, with inconsistent and difficult to learn move orders.

This is all to say I briefly tried the QGA out. More recently two short & sweets came out on chessable on the QGA and then a course for white that mentioned the difficulty of finding lines against the QGA, so we’re back looking at the QGA. Specifically I’d like to put together a quick starter repertoire that’s consistent enough to be quickly employable, and then, if some of the lines aren’t so strong, they can be subbed out. White has four main tries vs the QGA after 1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4:

a) 3.Nc3 the normal looking and inaccurate reply

b) 3.e4 the ambitious move I always struggled against

c) 3.e3 the standard move that allows …e5

d) 3.Nf3 the standard move that denies …e5

For consistencies’ sake I’d like to start by giving a quick plan for 3…a6 against all moves other than 3.e4. This post, which I’m writing first but publishing second, explores variations, while the first post will hone down to the easiest lines to learn with the most comprehensible ideas. Read that post! That’s the one where I do proper opening prep, this is the one where I get down a lot of variations but haven’t figured them out yet, much like the difference in my prep from an FM’s.

Continue reading Quick n Dirty: QGA Part 2Quick thoughts and I don’t have an example, but something I’ve been musing on. How and why do people mess up their calculations? I mean when the calculation can lead to clear material gains or checkmate, a tactic or combination rather than when the calculation leads to complex positional comparisons. I’m not thinking about evaluating, I’m thinking about how we screw up calculating forcing tactical lines, so I’m not really considering missing a quiet move in the middle or at the end either, that’s a different topic. So how do we screw up calculating tactical forcing lines?

I was recently skimming two books I’d like to discuss here, Pump Up Your Rating by Axel Smith and My System by Aron Nimzowitsch. In Pump Up Your Rating he gives the following position, black has just played 12…Nb4. You may try to solve for white’s best move if you like.

White to move – Olafsson-Averbakh Interzonal 1958

Continue reading ExchangesPositions you could try solving, under each will be a clue of the move type being looked for, you can scroll to the hint or not. All are tactical ideas from bullet/blitz games I played recently. The first one is prettiest but admittedly up a piece to start with:

Calculate a direct win

Simple and great is 1.Bxh7+ Kxh7 2.Qh5+ Kg8 3.Nxf7 threatening mate on h8 3…Rxf7 4.Qxf7+ winning b7 as well. But I was quite proud of 1.Nxc6 Bxc6 2.d5 exd5 3.Bxh7+ with the classic double bishop sac 3…Kxh7 4.Qh5 Kg8 5.Bxg7 Kxg7 6.Qg4 Kh6 7.Rf5 1-0.

Continue reading Some Interesting MovesA while ago a reader sent me a problem set they had worked on. I promised to look at it soon and give feedback and… then failed to do so. My bad! Apologies! Let’s look at some problems from it now.

As the intro points out, readers tend not to finish books. In fact, we tend to barely read even small portions of them! I love looking at chess books, I suspect I do more exploration than most, and yet still I am indeed guilty as charged. One thing that makes me bounce off books quickly is study like positions, usually mate in very few moves targeting a king on an open board where only the least intuitive queen move leads to the mate. Sadly for me, this file opens with such problems. So for now, let’s skip them. I may be deeply wrong but my experience is they’re exhausting, unrewarding, and unrelated to most chess play. So skipping those, I’m going to discuss the next few positions and stream of consciousness my ideas in them.

Our first position

Continue reading Problem SolvingI have hit a new all time bullet peak. Many think bullet is not remotely representative of broader chess skills, all mouse speed. I don’t think this is true, in part because I play on a touch screen. I have found when my bullet goes up that other forms of chess reliably corroborate the improvement. Let us assume it’s meaningful. This post will break down the chess work I’ve done over the past three months to get there and try to observe how impactful different study was. This will likely be very boring if you’re not me! But I do think there’s some studying ideas in here worth considering.

Continue reading Journey to 2696 (actually 2701, actually actually 2735)